April 19, 1955

April 19, 1955

OBITUARY

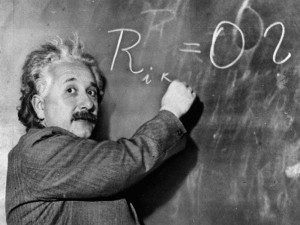

Dr. Albert Einstein Dies in Sleep at 76; World Mourns Loss of Great Scientist

By THE NEW YORK TIMES

Albert Einstein was born at Ulm, Wuerttemberg, Germany, on March 14, 1879. His boyhood was spent in Munich, where his father, who owned electro-technical works, had settled. The family migrated to Italy in 1894, and Albert was sent to a cantonal school at Aarau in Switzerland. He attended lectures while supporting himself by teaching mathematics and physics at the Polytechnic School at Zurich until 1900. Finally, after a year as tutor at Schaffthausen, he was appointed examiner of patents at the Patent Office at Bern where, having become a Swiss citizen, he remained until 1909…..

————————-

“Well, I was thanking Almighty God when that one was finally over with, I can tell you that. Couldn’t wait to get home and have a nice long shower. Almost nine damned years ago and it still gives me the creeps. I swear, if I have to explain relativity to one more person in one more system, I think I’ll probably just put a gun to my head.”

“Oh, come on now, Grant, it couldn’t have been all that bad. You should be getting rather good at it by now. What was that, your sixth time?”

“Doesn’t matter. Six times or sixty, nobody gets it. Hell, I barely understand it, and I’m the one stuck shepherding it around the bloody universe. And it doesn’t make me feel any better knowing that it’s wrong on top of everything else. It’s impenetrable and it’s wrong.”

“It’s not wrong, Grant. It’s merely… incomplete.”

“Incomplete? That’s one way of putting it, I suppose. Misleading, juvenile, borderline criminal—those would be other ways. So now, for the sixth time in as many centuries, I’ve got a civilization believing it’s impossible to travel faster than light.”

“A belief that will last them a good couple hundred years until they discover otherwise,” Hickok responds. “Oh, and lest we forget, if all goes well, it’s also a belief that will keep them from blowing up their feeble planet trying to do otherwise.”

“Yes, well, I pray they aren’t going to learn anything more from me. I mean, for God’s sake, we’re supposed to be advancing civilizations, not slowing them down. Tell you what, I’ve just about had it with this nonsense—every last bit of it. Actually I was thinking I might have a go at politics next time there’s an opening.”

“Best think twice on that one, mate. Talk to Billings sometime. He just got back from doing the Kennedy gig, and look what that got him. Brains everywhere.”

“And a damned fat bonus check, I’ll wager. Elected president, averts the Third World War, makes himself a martyr to boot. Some of these gigs, the best thing that can happen is a bullet through the head. Tears of a grieving nation, job well done, and you’re home thirty years ahead of schedule.”

I listened discreetly as Hickok and Grant bantered on at the next table about Grant’s last assignment on Earth. He sounded a good bit more disenchanted than he had following his prior assignments, but then, some are more taxing than others. Seems as though everyone gripes for a good while immediately following a field gig. Separated from your family for decades at a time, stuck eating earth food and dealing with earth logic and earth morality. But then a few years go by and they’re invariably ready for the next assignment. At least they’re out there—in the shit, as someone on earth used to say. Me, I’m stuck here at home—Trent Stephens, stalwart Senior Analyst in the Historical Archives Department, documenting for posterity all the interventions I wish I was out there doing for real, in person. I don’t mean to suggest that it’s all bad. I get to interview presidents, scientists, musicians, basically everyone who’s ever made a significant contribution to history on earth for the past three thousand years. This is, after all, what we do—grease the wheels of civilization whenever and wherever they get a little sticky, which is more often than not on a planet like Earth.

“But hey,” Hickok interjects. “You got a nice obituary out of it. Hell, you even won a Nobel Prize, right? There’s a nice little bit of recognition, eh?”

“Yeah, awesome,” Grant replies, feigning disgust. “That and a couple of bucks will get me a cup of coffee. Talk to Fleming about Nobel Prizes. He’s got four of them last I heard.”

“Four? Are you serious?”

“Yeah, and all physics. Remember, he was Curie, Bohr, Dirac, and Fermi.”

“Hmmm. Busy guy. Guess once you get good at something, you risk getting type-cast, huh?”

“Which is why if I’m going to make a move, it probably needs to be now.”

And on they went, comparing interventions, awards, what it was like living in different places on earth, the wives, the houses, everything. Our race operates pretty much like any company anywhere. There are your front-line guys like Grant and Hickok. They get field assignments and spend most of their lives on the road. Then there are support guys like me who hardly ever travel—research, recruiting, accounting, that sort of thing. No real chance of my getting into the field rotation. Best I can hope for is a position in Planning and Scheduling. They monitor each civilization’s progress against preplanned goals and objectives and dispatch field reps whenever a new discovery is called for, a cultural upheaval is needed, a war needs starting or stopping, the big things that keep progress progressing. Earth didn’t even get on our radar screen until about three thousand years ago, around the time they started writing and communicating with each other in a reasonably intelligent way. Heck, if it wasn’t for us, they’d still be living in caves and making arrowheads out of pieces of flint.

“So when are you out again?” Grant asks from behind his menu.

“Looks like a couple months at the earliest. I’ve actually been out and back while you were off playing Einstein and winning Nobel Prizes.”

“Really? And still in Philosophy and Religion? What was the gig?”

“Seventeen years as Pope Pius XI, if you can believe that.”

“No kidding? That was you who founded Vatican City as a country?”

“Guilty as charged. Seemed like a good idea at the time. I guess we’ll see how it works out.”

A few basic things require explaining before we get much further. I said our race is run like a company, like an Earth company as it happens, though that almost makes it sound like we modeled ourselves on what Earth does, when, of course, it’s the other way around entirely, seeing as how we’ve been in this business for at least a hundred or so of their millennia. In fact, the reason Earth companies (and companies all over the galaxy, for that matter) operate like they do is that many of their founders were our field operatives who naturally brought our business structures and strategies along with them on their intervention assignments. But like any business, our field reps are measured against a set of performance goals that determine everything from compensation to future assignments. Of course, like any service company, the principal measure is utilization, the percentage of time they spend in the field serving in some leadership capacity, versus waiting at home for the next gig, being “on the beach” as the consultants like to say. Another key measure, one that Hickok alluded to in some of his earlier comments, is the natural to unnatural death ratio (UDR). As a general rule, unnatural deaths are frowned upon from a ratings and performance perspective, though some allowance is, of course, made for the higher risk positions such as Third-World rulers and military officers. And then there’s the new policy memo that was circulated just a couple of days ago.

“So, what’s the story with this new suicide policy I’m hearing about?” Grant asks, casting his eyes about the restaurant, increasingly frustrated at his inability to engage a waiter with eye contact. “I hear it’s got everybody all in a lather.”

“Especially the guys on the artistic side, wouldn’t you know. Folks upstairs got a little spooked, I think, over the Hemingway thing. Everybody felt as though Fitch unilaterally shaved twenty-odd years off his gig while still getting full marks for artistic contribution, etc, etc. That was followed by a spate of copycat suicides, mainly writers and musicians. They were leaping off bridges, sticking their heads in ovens, all sorts of unpleasantness. Finally management got fed up and decided to put the kibosh on the whole thing. Now you off yourself and you sacrifice your entire point allocation for the assignment, simple as that. They’ve had maybe six guys bolt from Music and Writing just this week over it.”

“Bolt and go where?” Grant replied. “What’s a career writer or musician going to do other than be a writer or musician?”

“Fair question, my friend, and one I have no good answer to. But I can certainly understand why they’re hacked over it. Who the hell could spend fifty years writing books or concertos, for God’s sake?! Hell, I’d throw myself in front of a bus too. All the brouhaha may, though, have an impact on you trying to get out of Physics and Chemistry anytime soon. Best you stay current on your math and science, I’m afraid.”

It would be easy to get the impression from all of this that humans are a hopeless collection of dolts incapable of innovating anything on their own without help from outside or that governing themselves without descending into civil war every ten years is beyond their ability. It’s not as though there aren’t some genuinely clever ones amongst them. It’s just that there are so damnably few and there’s so much to get done in such a short time if they’re going to advance at a reasonable pace. If we’d waited around for them to figure out gravity, thermodynamics, and cosmology on their own, they’d still be drawing on cave walls. As it is, we tend to mete out our field assignments based on an assessment of how well the race is handling things on its own. Sadly for humans, progress got off to a late start and hasn’t shown much sign of improvement since. And, like it isn’t difficult enough keeping things moving with our own staff of on-site interveners, we even have to step in and undo some of the biggest nonsense that the humans manage to think up on their own. Case in point, Clive Baxter goes out in the second half of earth’s sixteenth century and invests nearly fifty years getting Galileo on track, only to have a human-led Catholic Church do its level best to overturn nearly everything the poor guy did. We intervene with twenty-four consecutive popes, and then one human sneaks in and nearly sets everything back a century. Honestly, with humans, you can count all the genuinely notable achievements they’ve come up with on their own on one hand.

“Hell, Hickok, it’s so damned mindless. That’s what tears me up the most. Forty or fifty years at a go. Nothing but insufferably boring conferences, symposiums, papers, and spending your days with humans who think they’re so damned original. I can’t wait ‘til they reach that fateful traumatic day and discover that there are thousands of other races floating around in the ether who’ve discovered all the same shit they have, only lots more of it. Then we’ll see how original they are. Meanwhile, we’re the ones figuring all this stuff out and meting it out like so much cat food. It’s borderline humiliating, I tell you.”

“So you’d rather be back here doing the actual research, figuring out the genuine new stuff?”

“Good God, no. I never had the test scores for that. All my top marks were same as yours, same as all field reps—communications, negotiation. Hell, Hickok, we’re glorified salesmen, except the people we’re selling to don’t know they’re being sold to.” He finally attracts a waiter by the expedient of standing up and waving his arms.

Hickok smiles wryly as Grant retakes his seat. “All the knowledge of the universe, but we can’t figure out how to do decent service in a restaurant. Now there’s something the humans have figured out, some of them at any rate.”

Grant peers again at his menu as the waiter, clearly put out by Grant’s histrionics, approaches. Grant looks up at Hickok. “What’s good here? I haven’t been to this place in years.”

“Nothing’s changed. You should know that. Nothing ever changes. Last time they updated the menu here, Napoleon was still busy conquering Europe.”

The dialog seemed so trite, so banal, over dinner. Yet these men—not only Grant and Hickok, but all field operatives—possess one additional skill that Grant failed to mention in his manifest of intervener capabilities. It is the skill—innate ability is a more accurate descriptor—that enables interventions to take place at all. There is a word for it in our language, several words in fact, but none quite captures the true essence of this skill, this gift. Closest that would convey to a human is absorption. Field operatives, who turn out to be about fifteen percent of the population of our race—are born with the ability to separate mind from body for extended periods of time, leaving behind a body in stasis while their minds travel great distances. In addition, and even more to the point of intervention, they can insert their minds’ contents, their very consciousness, into the mind of another, in essence taking over the personality and thoughts of that individual until such time as the intervener chooses to depart. It is this ability, and the combined knowledge of our civilization, which has existed in this state for many hundreds of millennia, that has placed us in the position we now occupy in the galaxy, viz architects of development for the civilizations in our portfolio. It is a righteous calling, the very essence of civilized life itself, yet Grant and Hickok (and many others like them, for I have overheard many such conversations) make it sound like a drudge.

“Damn it, Hickok, anybody could do this job, anybody with the good luck to be born to the right set of parents and test appropriately once they reach a hundred years. You take the bloody test, you score in the ninetieth percentile, you pick a discipline, and you sit through a couple weeks of info download. My cat could just as well have done Einstein, for God’s sake. Toughest part would’ve been getting the data download probes to fit on his furry little head.”

Some of the field reps are more inclined than others to sprinkle their dialog with religious aphorisms. Religion itself is a useful bit of chicanery someone thought up a few millennia ago as a means of keeping developing races on a more easily controlled path of development than might otherwise have been the case. It’s a particularly delicate assignment when Planning and Scheduling determines that it’s time to create a new religion and/or a new pseudo-deity. It’s not terribly popular with the interveners either, since many of these gigs involve a good bit of persecution, both physical and mental, and many of them end in a painful martyrdom of one sort of another. All of which explains why the guys who’ve built their field careers around work on Earth tend to throw around ‘God’ this and ‘Jesus’ that in their everyday conversation. Last I heard, Bernard Higgins, the fellow who did the original Jesus assignment, had retired from field work and parlayed his borderline legendary status as progenitor of Christianity into an executive role, something in Finance I think. I never met him, but word among the other field reps was that he was a bit of a whiner and a sycophant, traits that may come in handy upstairs. Interesting historical side note—the field rep who was Buddha also drew the Muhammad assignment some years later. Same guy.

“It’s not as mindless as you make it out to be, Grant. You’re not giving yourself—or your fellow field reps I might add—nearly enough credit.”

“Well it isn’t exactly brain surgery, my friend. Hell, I could take a quant jock from Finance or a damned research analyst down there, plug them in, and no one would be any the wiser. I’ll bet they’d do fine without even getting a data download first. Hell, to get out of grade school here you have to know more than anybody on earth will know for another thousand years.”

“True enough,” Hickok agreed, “but it’s not so much what you know as what you do with it.”

“Here’s a deal for you to think about. You get me a political assignment, and I will bet you dinner at the restaurant of your choice that I can take any entry-level Analyst you choose out with me, plug him into the role, and he’ll do no worse than the average full-time intervener.”

“Get the hell out of here. For starters, you’d never get it past Staffing. You take an Analyst out into the field and they’re only allowed to have a role that works directly for you. You’re responsible.”

“Fine. So we get to the job site, we swap places for a few years. What’s the worst that could happen? I take a functionary role working for him, so I can keep an eye on things.”

“My choice of restaurant and hapless Analyst? Sounds like money in the bank. But remember, if he starts a nuclear war, I had nothing to do with it.”

At which point, they, needless to say, have my full attention. The chance of a lifetime and all I need to do is be hapless? Steeling my nerve, I glance about the restaurant in one final moment of uncertainty. Checking that my distinctly blue Analyst badge is prominently displayed on my lapel, I rise from my seat, lift my glass of wine, and step toward Hickok and Grant’s table, where I feign a trip and deposit the wine unceremoniously into Grant’s lap. He leaps back, surprised and appalled, wiping feverishly at his shirt as Hickok grins.

“Aw shit, sir. I am SO sorry. Let me get that.” I snatch additional napkins from unoccupied tables.

“Just leave it….leave it,” he replies in disgust. Hickok notes my badge and I see a look of satisfaction come across his face.

“They overworking you in Research, son?” he asks.

“Yes, sir,” I stammer. “I’m pretty beat. I was … up most of last night finishing a report. I’m really sorry, sir.”

“Pull up a chair, Stephens. My colleague and I have an interesting idea we’d like to bounce off you.”

All of which is a long way of explaining how, three months later, I found myself on Earth, in the person of Richard Milhouse Nixon, thirty-seventh president of the United States, with my most trusted advisor, the man in whose lap I had poured an entire glass of cabernet, John Erlichman/Grant. It was an interesting and instructive few years, but when all was said and done I was happy to get back to the Research Department and Grant was even happier to return to Physics and Chemistry, despite having to buy an extremely expensive dinner for Hickok.