~ Reflections on Just How Badly the Game of Golf can be Played ~

~ Reflections on Just How Badly the Game of Golf can be Played ~

I have wanted to write about my views on the game of golf for quite a long time, but always resisted for one reason or another, not least because so many others more talented than me have made such a splendid job of it[1], leading me to conclude there was little I could add to the dialog. Only then, after a bit of reflection, I finally hit upon a potentially unique angle. Most of the extant golf literature is either about the subtle grandeur of the perfect drive, or the mist floating gossamer-like across the first green at sunup, perhaps even the ephemeral serendipity of a hole-in-one. But no one, so far as I could tell, had ever reflected (at least not publicly) on just what it meant to suffer through an entire lifetime of truly wretched, mind-numbingly bad golf. I could be that writer.

Because golf is such a painful topic for me, I do not plan to edit this treatise or revisit it in any way once I’ve suffered through writing it all down. Therefore, if the whole affair has a disjointed, stream-of-consciousness feel to it, that’s because I opined on the various aspects of the game more or less as they occurred to me, and I don’t think I can bring myself to read it all again. I should mention, as well, that because so many have plowed this rhetorical field before me, and have done so in far more eloquent fashion than I can hope to achieve, I mean to shamelessly plagiarize their finest words with the occasional quote, an objective I’ve embraced right from the start, i.e., in the very title of the essay, which the astute reader will recognize as Mark Twain’s trenchant and concise summary of the game.

Given that my tone throughout this analysis, indeed already, will seem to some a negative one, the logical question will arise, “if he dislikes the game so much, why in the hell doesn’t he just stop playing, quit whining about it, and get on with his life?” If only it were that simple. If you have never swung a golf club, then by the end of this treatise, you will understand why that is such a difficult question to answer. If you play regularly, but are not good enough to be making a living at it, then you already know the answer. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I should state at the outset, by way of providing a bit of over-arching context, that I do not much like the game of golf. There are more reasons for this than I can possibly enumerate or expound upon here, though I hope to touch on the most important ones. I do not like it at a personal level, the primary reason being that I am so profoundly awful at it, the reasons for which are complex and nuanced and which will comprise the lion’s share of the exposition to follow. I also do not like golf for a number of societal and professional reasons, but these are secondary to my principal thesis and I’ll come back to them in the summary.

So here we are already, back at the same vexing question—why does a reasonably sentient individual repeatedly engage, apparently voluntarily, in an activity he neither enjoys nor is any good at. Fair question. The short answer is that I play only very infrequently (perhaps three or four times a year) and only when asked by a friend or colleague[2]. I certainly don’t like it enough to go out on my own or to initiate a round myself. So it’s really more of a social event than a sport in any meaningful sense of that word[3]. Still, the pain is real, for if there’s one thing worse than playing bad golf, it’s playing bad golf when there are other people around to see.

But that’s a bit of a cop-out answer, truth be told. For if a friend asked me to join him skydiving, I would politely decline and go about my business[4]. The ugly truth of the matter is that I go (when asked) because I manage to convince myself that the four or five hours required to get through a round might, this time, be pleasant, or at least bearable, particularly if the weather is nice, the course is well-regarded, and the friends who’ve asked me along aren’t so good at the game that I risk genuinely annoying them with the enormity of my inability[5]. So how is it that I could manage to fool myself on this matter, given my years—decades actually—of experience? Well, here’s the truly insidious aspect of golf in a nutshell: no matter how profoundly one sucks at it, by simple law of large numbers[6], everyone hits a great shot once in a while—everyone.

It might be that after whiffing in the tee box twenty consecutive times, on the twenty-first swing you hit a Daley-esque three hundred yarder straight down the fairway. Or perhaps you chip one into the cup from eighty yards off the green. Whatever the shot, however improbable, it will be suitably spectacular and unexpected that instead of exhibiting the correct reaction, i.e., “Wow, what an incredibly lucky shot. I guess statistics really works,” the bad golfer instead concludes, “Wow, that was easy. Looks like I’ve finally got this game figured out[7].” And that’s when the trouble starts.

Because golf is so painful for me, and because, on top of the emotional pain it also costs rather a lot of money to play, this is prime real estate for a terminal case of cognitive dissonance. I’ve expounded on this psychological phenomenon in other writings, but it’s worth a quick review. Cognitive dissonance is that effect whereby we convince ourselves of the merits of something which, in fact, is without merit, so as to avoid feeling like an idiot for paying for things that ultimately prove to be painful, worthless, or both. And since convincing myself of the inherent merits of golf requires epic leaps of fantasy and imagination, the task is made much easier if I simply delete from my memory all of the horrible shots I’ve made in previous rounds[8] and focus instead on only the meager handful of respectable ones. This, in addition to allowing me to trick myself into thinking that the next round will be pleasant and rewarding, also has the added benefit of taking up far less mental space, since the incidence of decent shots are so very few. So, in summary, the reason I am able to steel myself to play each new round of a game at which I am so apocalyptically bad is because I have the not-at-all-unique mental ability to remember only the good aspects of past games[9].

Which brings us at last to the single most critical aspect of golf, the mental game. Success in golf has nothing[10] to do with swing style, arm strength, aim, or anything else mechanical. It is, simply, the ability to play every swing as though it were your first of the day, even if every preceding shot has ended up in the woods, the water, or at the bottom of a ten-foot-deep pot-bunker. There is much talk among golf coaches about the benefits of so-called muscle memory, that physical human facility for replicating a motion so frequently in practice that you do it the same exact way every time when you’re playing for real. That’s all well and good, but the other kind of memory—the real kind in your head—has a precisely opposite and deleterious effect and does more to discombobulate golf games than all other sources of distraction combined. And therein lies my biggest problem.

I have two principal problems with participatory sports. First, I am utterly uncoachable, i.e., nothing a person tells or shows me, no matter how impeccable their credentials, will have the slightest impact on how I actually perform the sport or game. My standard approach to everything athletic, including not only golf, but skiing, distance running, tennis, baseball, and a host of other pursuits, is exactly the same: 1) Go buy some really good equipment, 2) start playing, 3) quickly develop some really bad habits, 4) almost as quickly, reach a plateau of performance described favorably as intermediate or pejoratively as mediocre, and 5) remain there for the rest of my life. The second problem with me and sports is that once I make a mistake, it remains with me psychologically for at least the duration of the particular game in question, and frequently for days after that. Doesn’t matter whether it’s a dropped fly ball in center field, an easy baseline tennis shot hit into the net, or a golf ball vigorously shanked onto the next fairway. Stated simply, once I’ve made a mistake of any kind with a golf club, every shot thereafter is diminished by the incessant recollection of, and fulmination about, that mistake. And since this effect inevitably causes yet more mistakes…well, you get the idea.

Once my performance begins to deteriorate in any particular round of golf,[11] I quickly sink into a well of depression and despondency so complete that every shot thereafter is pure unbridled futility. A good friend and golfing partner once made the cruel observation (later verified with the aid of a video camera) that, once my game has gone south, I so convince myself of how awful each subsequent swing is going to be that I frequently shout “Shit!”, or other appropriate invective, on the downswing before my club head has even made contact with the ball. Talk about your self-fulfilling prophesies. Which is, I suppose, a good enough segue into the subject of language as it relates to the game of golf.

Ray Floyd, aside from having an outstanding short game, also had a way with words. He gets credit in golfing history for speculating that the reason the game is called “golf” is because all the other four-letter words were taken[12]. Well, Ray certainly knew what he was talking about. There are few sports, either team or individual, in which language plays so pivotal a role. And I can state here, for the record and without fear of contradiction, that florid language is the one aspect of the game of golf at which I have few equals, in either the amateur or professional ranks. It may have something to do with the fact that I have a good vocabulary from reading and writing a lot, or perhaps it harks back to all that time I spent in the military, but I take rather a good deal of pride in both the quantity and quality of my golf-related vituperation. Indeed, if there were only some way of working it into the official scoring, my game might actually be worthy of calculating a handicap. Sadly though, there are no points awarded for colorful verbal exposition.[13]

Interesting side note—whereas I limit my emotional expression to the linguistic, many others (including my aforementioned friend) not only wax fairly eloquent in their own right, but exhibit, as well, a wide array of supplementary physical displays which, while doing little to improve their game, often provide quite stunning entertainment. These displays include falling to one’s knees and gazing to the heavens in futile supplication, and heaping various forms of abuse on one’s golfing equipment, including, in extreme cases, actually destroying it, either through repeated contact with trees and other immovable objects[14], or even through the unlikely expedient of pitching it into the nearest pond.[15]

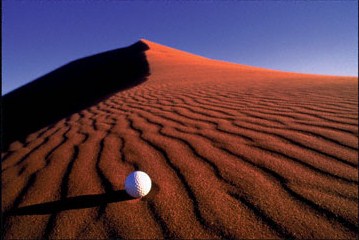

Of course, the greatest single source of frustration in golf is the fact that it is the only sport, so far as I can determine, in which the ball is not moving at all while one is attempting to strike it. There is no shame in swinging at and missing a ninety-mile-per-hour Roger Clemens curve ball or failing to catch a Tom Brady pass. But to stand and stare down at a small white ball[16] perched arrogantly, tauntingly, on a wooden tee, knowing that you have all the time you need to prepare yourself before swinging, is the very epitome of induced stress[17]. It’s worth noting here, as well, that the tee shot is almost certainly the most stressful of all the various shots one is called upon to make during the course of a round. This is because, unlike all of the middle-game shots, many of which you are making relatively far away from your colleagues, i.e., where they are less likely to witness your incompetence close-up, the tee shot takes place with your three friends standing close by, gazing with rapt attention upon your every move. If you’re Tom Watson, the others are staring at you in hopes of learning something that will improve their game, If, on the other hand, you’re me, they are staring in expectation of some colossal blunder that will lead to raucous hilarity and break up the otherwise monotonous ebb and flow of the game.

Someone once said that, in football, when the quarterback throws a pass, only three things can happen, two of which are bad. This pithy bit of folklore applies, in more or less similar fashion, to swinging a golf club as well, except that the odds in your favor are a good deal worse than the thirty-three percent that apparently applies in football. When you swing a golf club (presumably at a golf ball; other reasons for swinging a golf club are squarely outside the purview of this essay), any number of outcomes can accrue, all of them bad save for one. The desired result is, of course, that the club face strikes the ball squarely and the ball flies straight and true toward the green or cup. Possible less ideal outcomes include: a) the ball slices meanly to the right, b) it hooks savagely to the left, c) it starts flying straight and upward but then dives violently downward into the ground[18], d) it climbs to a vertiginous height and then lands, straight and true, five or ten yards in front of you, e) you hit the ball in more or less the intended direction only to have it land in one of the various hazards placed conveniently between you and the green, f) you hit the ball straight, only to have it impact a tree or other immovable object and carom in some unintended and less than optimal direction, and my personal favorite, g) you miss the ball entirely[19].

There are, of course, any number of reasons for all of these bad outcomes, nearly all of which can be filed under the “lack of basic skills” category. It’s important to note, however, that only a portion of golfing skill is determined by what happens once the club begins its motion. There’s an entirely different set of challenges associated with getting the club properly in your hands to begin with. Stated simply, every aspect of how to correctly grip a club, and hold your arms, head, and feet, is constructed so as to feel as unnatural and uncomfortable as humanly possible. It has even been posited by more than one golf pro that if anything about your posture or grip feels in any way comfortable, then you have it wrong. And since most of the people you will play golf with are amateurs like yourself, each will gleefully tender their own advice on just what is wrong with your stance, grip, posture, and swing. They will exhort you to keep your head down[20], open/close your stance, interlock your fingers on the grip, align your thumbs, bend your knees, keep your elbow straight, and, in the end, offer so many ultimately self-contradictory admonitions that by the conclusion of the round it will be a wonder if you can manage to walk back to your car in the clubhouse parking lot.

But back for a moment to this business of manmade hazards, by which is officially meant bodies of water, sand traps, grass allowed to grow very long (“rough”), and various other obstacles intended to infuriate and generally slow things down. The skilled golfer, of course, for the most part avoids these impediments entirely, whereas the unskilled golfer is drawn to them like the proverbial moth to a flame. Each presents its own special challenge, with water being perhaps the easiest, only in the sense that ninety-nine times out of a hundred, there is no shot and you simply take a drop, add a stroke and go about your business. The most truly unnerving hazard is easily the sand trap, a contrivance of Satan himself, as evidenced by the countless invocations and blasphemous utterances that attend someone endeavoring to extricate himself from one.

There are a few unique aspects of landing your ball “on the beach,” as the sand trap is endearingly known. First is that you are not allowed any practice swings. You simply stand before the ball (“addressing” it in the vernacular) and take your swing, for better or worse. And then, following the dozen or so attempts it can take you to get out of the sand, you are expected (as though your principal concern at this moment is for your fellow golfers) to take up a nearby rake and smooth over the numerous shoeprints and foot-deep divots you have made during your expedition. Without dwelling too much longer on the painful topic of sand traps, let me close by observing that there can be no single more infuriating action performed by mortal man than having your fourth or fifth swing from the same sand trap sail smoothly up and out, precisely as it’s supposed to, only to fly cleanly over the flag and into the other sand trap on the far side of the green.

I indicated earlier that there were elements of golf I do not like that have nothing whatsoever to do with my own particular brand of incompetence, elements that are simply annoying in their own right. These can all be loosely collected up into the general category of rules and etiquette. Countless books have been written on the rules of golf, and suffice it to say that the individual regulations are beyond arcane and number in the thousands. It is not my intent, of course, to expound on all of them here: only to say that taken in their totality, they add an irritating undertone to a game that’s already plenty irritating to begin with.[21]

It is, by the way, important to distinguish between honest-to-God rules and historically accepted etiquette. Into the former category fall items such as not moving the ball once it has stopped so as to improve your lie, not moving objects out of the way of a ball that is still moving, not carrying more than fourteen clubs in your bag, etc. Into the latter category fall two subcategories, the first of which is rather like rules, only not quite. These include infractions such as standing on the green so as to cast a shadow across the line of a putt your colleague is attempting, or, prior to that same putt, walking on the grass directly between the ball and the cup[22]. Into the latter subcategory fall more entertaining traditions such as dropping your pants following any drive that fails to travel past the ladies’ tee box, conceding a putt to an opponent when it is close enough to be regarded as a “gimme,[23]” and, of course, the “mulligan.[24]” These latter items are all in good fun and no one takes them terribly seriously. The actual etiquette items, though, can and frequently do generate actual animosity, or at least a glowering stare, if infringed upon. If you don’t believe it, try picking up another player’s ball or sneezing just as one of your foursome is teeing off.

Oh, and lest I forget, there exists one more gentlemanly tradition that is particularly annoying to the seriously bad golfer. Following the drive, and on every subsequent series of shots until the putts are completed, it is customary to allow the golfer farthest from the pin to shoot first. When, as is frequently the case with me, you are playing with others who are significantly better than you, it typically means that you get to go first on nearly every series of four shots. If you’re really bad, so much so that your, say, second shot fails to even catch you up with where your partners were following their first shots, you will endure the ignominy of hearing the three most horrific words in all of golf—“it’s still you.”

In closing, it is worth opining, if only for a moment, on the societal aspects of golf. I can’t expect to gain much credibility with these objections, because if I found my own arguments compelling, then presumably I wouldn’t go near a golf course. Still, it is worth explaining why so many hold the game in such contempt. One element that always bothered me throughout my professional career is that, to this day, there exist many Fortune 500 corporations in which you cannot hope to advance beyond the ranks of middle management unless you are an avid and proficient golfer. It is still extremely common to do deals and conduct networking on the golf course, and I have taken such pains to avoid this conduct throughout my life that it accounts, at least to some degree, for my never having been elevated to the executive ranks[25]. There exists also the strong whiff of elitism that attends the sport. It took the arrival of Tiger Woods to put to rest the notion that golf is a sport for the exclusive enjoyment of wealthy white people. And, Woods’ impact on the game notwithstanding, it is still a fairly expensive undertaking, and unavailable to a very large swathe of the population. Finally, an issue that vexes me from time to time, when I bother to stop and think about it, is the egregious waste of real estate that attends the construction of any new golf course[26]. With all the homeless people roaming about the country, it feels more than a little crass to utilize so much land for what is, ultimately, a pretty vacuous purpose.

And so here we are, back where we started, without perhaps having satisfactorily answered the irksome question of why a reasonable person would repeatedly undertake an activity that has so little to recommend it (and then write about it, for God’s sake). I can only go back to that business about one good shot in a million. It’s enough to keep you coming back. Hell, for many people (present company excluded) it’s even enough to keep you springing for expensive new golf gear every year or two. One final topic that didn’t get addressed above is ethics, specifically the fine art of cheating on one’s score card through expedients such as, for example, neglecting missed shots that no one in your party happened to see but you. Of course no one who plays the game is above an occasionally creative interpretation of the rulebook. Still, in the end, you’re only really cheating yourself. For me, the game is so consistently annoying that I’ve typically stopped keeping score by the back nine anyway, after which the whole thing inexplicably becomes a lot more pleasant.

[1] John Updike comes immediately to mind, though there are countless others who have tackled the topic with verve.

[2] I will occasionally participate in a charity event as well, but these are almost always done in a scramble, or best-ball, format, and so do not rely, to any appreciable degree, on one individual’s skill level. You simply make sure that one of the individuals in your foursome knows what the hell he is doing. That reduces the entire affair to an excuse to ride around in a golf cart and drink beer for four or five hours.

[3] Someone once said that any sport in which a 60-year-old can beat a 30-year-old is no sport at all.

[4] Bad example actually. Whereas golf requires actual skill and assorted other attributes to be discussed shortly, skydiving, as far as I can tell, never having done it, requires only that one succumb to the force of gravity (well, that and having the cojones to step out of the plane in the first place), which, in my extensive experience, requires not much effort at all. Oh, and you also require enough arm strength to pull the rip cord at some point during your descent, without which capability the whole affair ends in a rather unpleasant fashion.

[5] Mercifully, I have quite a number of friends who are also pretty bad at golf—not as bad as me, by any means, but bad enough so they don’t care to be seen playing in public with anyone except me.

[6] Or other obscure mathematical construct, which may or may not be germane to the argument.

[7] Ever notice how when you walk up to a set of double doors you always tug on the wrong one first before opening the one they’ve left unlocked? Even though you get it wrong and wrench your elbow out of joint twenty times in a row, opening the right one first just once keeps you coming back. Same idea…

[8] Understand, we’re talking very large numbers here.

[9] Lest the reader doubt my continuing assertions as to just how badly I play golf, I started approximately twenty-five years ago, and, despite playing an average of four or five times a year (which admittedly, isn’t frequent enough to get any better), I have never once broken 120. That’s saying a lot when the typical course is a par 72 and PGA rules require picking up your ball once your stroke count reaches double par for each hole, meaning that, strictly speaking, it’s impossible to exceed a score of 144, even if you never once made contact with the ball.

[10] Or very little, at any rate.

[11] This often begins right from the first hole, but occasionally doesn’t get going in earnest until several holes have gone by.

[12] Before we get too engrossed in the topic of florid golfing language, let me observe here that it must be a frustrating thing indeed to be a professional golfer and to have to verbally contain oneself after an egregiously bad shot. Given the general quietude of a typical broadcast golf game, it would be quite something to hear Tiger Woods let loose with an f-bomb following a drive into the water. I don’t know—perhaps these are just edited out.

[13] Noted 19th-century British amateur golfer Horace Hutchinson wryly observed “If profanity had an influence on the flight of the ball, the game of golf would be played far better than it is.”

[14] “They throw their clubs backwards, and that’s wrong. You should always throw a club ahead of you so that you don’t have to walk any extra distance to get it.” Tommy Bolt, notably effusive professional golfer nicknamed “Thunder” for the vigor with which he routinely hurled his equipment.

[15] I once watched a distraught fellow (not in my foursome) actually smash his forehead repeatedly against the steering wheel of his golf cart.

[16] Diameter – 1.68 inches. Weight – 1.62 ounces.

[17] Yet more stress is occasionally induced when you’re playing on an over-crowded course, so that the foursomes back up against each other. That means that not only are the other members of your foursome watching you, but there will frequently be one or two additional groups watching as well, all of them irritated that you are delaying their game by taking so long to complete your shot.

[18] This disconcerting effect is the result of so-called “skulling” the ball, meaning that, rather than strike the ball squarely, you instead grazed the top in such a way as to impart enormous top spin—same effect as what a good tennis player does with a deep-court forehand volley, only he’s doing it on purpose and to good effect.

[19] This final ignominious outcome can actually happen in one of two ways. You can either swing cleanly through and simply make no contact at all with the ball (though if you miss by just a hair, the breeze from the passing club head can cause the ball to fall off the tee). Or you can swing so as to cause the face of your club to impact the ground behind the ball, bringing the whole effort to a painful and rather violent conclusion the only result of which is a significant divot that will require repairing. To add insult to injury (physical or psychological), PGA rules count these futile efforts as legitimate strokes, despite the ball having made no forward progress at all.

[20] By far the most common advice received by amateur golfers has to do with failure to keep one’s head down. The problem arises from the perfectly understandable tendency to want to see where your ball is headed once you’ve struck it, particularly in the unlikely event that it turns out to be an excellent shot. One of the many small sources of annoyance in the game is finally striking the ball decently and then not even having the pleasure of seeing it fly.

[21] Here’s a fun and obscure regulation: Rule 19-2b states that if a golfer hits himself with his own ball during the course of play, a two-stroke penalty is administered. Or try this one on for size: According to USGA definitions, holes made by burrowing animals such as groundhogs or rabbits are considered abnormal ground conditions and are subject to relief (meaning you get to move the ball to a more propitious location). However, holes made by dogs (or other non-burrowing animals) are not considered abnormal and therefore, no relief is available.

[22] Which footfalls (particularly if you are wearing spiked shoes) could alter the surface so as to change the ball’s subsequent speed and/or direction.

[23] “A ‘gimme’ can best be defined as an agreement between two golfers, neither of whom can putt very well.” Author unknown.

[24] Storied tradition in which each golfer is entitled to one “do-over” shot of their choice. Strictly-speaking, this can be applied to any shot, though the vast majority are used on errant drives. I attempted a bit of research into the origin of the term, only to conclude that none of the several extant explanations has any hard historical backing. Thus, we will note, without prejudice, that Mulligan is a common Irish name, whereas golf itself was invented by Scots, their neighbors to the west. Noting the frequency with which immediate neighbors get along in world affairs, and combining with this the desire to affix a lasting and pejorative sobriquet to an element of their new game…Well, I think you can do the math on that one.

[25] In fairness, I should clarify by saying that this is merely symptomatic of a more general tendency on my part to eschew anything that could be construed as politically-correct corporate behavior. I’ve always hated the idea that corporate advancement should depend on anything aside from one’s job performance, but the sad reality is, alas, quite different.

[26] The average golf course comprises 150 acres, of which half are typically manicured, groomed, or otherwise maintained.